By: Ellen Leibsly, M.S., CCC-SLP

Have you ever used an AAC before? The odds are that you probably have! Sending an email and writing notes are both things we use daily to facilitate communication without using our voices. But what constitutes an AAC?

What is an AAC?

AAC stands for augmentative or alternative communication. Augmentative means that it can be added to someone’s speech capabilities. This could include those who have difficulty using their voices to communicate on a consistent basis. Alternative means that it is consistently used in place of speech to communicate.

Categories of AAC

AACs are primarily identified in the following ways: low/high technology and aided/unaided.

Low-technology AACs include writing, drawing, and spelling words by pointing to letters on a communication board, pointing to photos/words on a communication board, or giving photos/word cards to a communication partner, etc. High-tech AACs often utilize some form of tablet/device and can come with speech-generating capabilities.

Unaided AACs include non-spoken means of communication that people naturally use. These can include facial expressions, gestures (e.g., nodding your head or pointing), and American Sign Language. Unaided AACs require a communication partner who can interpret and determine what the user wants to communicate. In this blog post, we will be focusing on aided AACs; these are AACs that require external materials and supports.

Types of AAC

Aided AACs include, but are not limited to, the following examples:

Buttons

To utilize buttons in isolation (i.e., not connected to a tablet/device), a communication partner can record a message, such as “more,” “yes/ no,” (if two or more buttons are available), etc. Buttons in isolation are typically an option for individuals who cannot rely on fine motor capabilities to activate a tablet/device or those who benefit from having fewer options available.

Buttons can be beneficial because they easily demonstrate the cause-and-effect nature of language and are often the simplest form of AAC to use on their own. They also require less advanced fine motor skills to activate.

On the flip side, buttons used in isolation for communication can provide limited options for the user, as the communicative intent is often predetermined by the communication partner. Furthermore, if a button is used to activate a tablet, they can be more time-consuming. With this form of use, the user typically needs to wait for the desired row/option to be presented before hitting a button to select.

Tablet

Tablets are utilized for individuals who benefit from having increased options or want the ability to have more options introduced later on. These individuals must have the fine motor or oculomotor (for an eye-gaze device) capabilities to use this form of AAC appropriately.

Tablets offer a more comprehensive array of communicative functions as well as increased independence for the user. They also require increased time to teach and master. Additionally, the user’s fine motor or oculomotor skills must be more advanced and consistent.

PECS (Picture Exchange Communication System)

PECS are often utilized with individuals on the Autism spectrum. This system is unique in that it typically requires increased interaction with a communication partner to use.

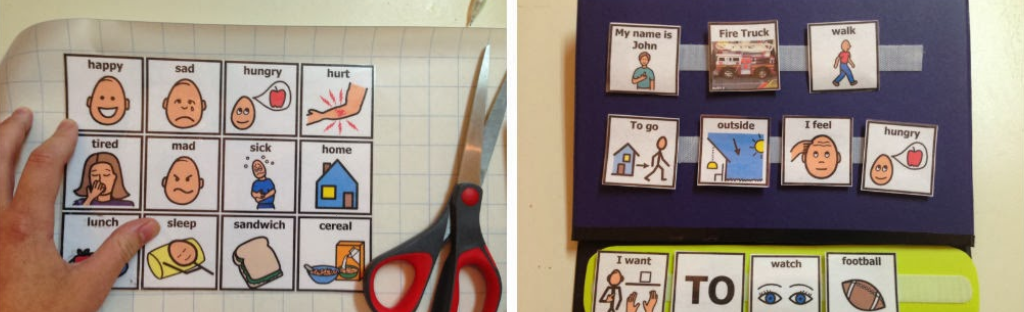

It works by having a page or book of pictures/icons available that the AAC user can give to their communication partner. As language and communication skills advance, they can utilize a sentence strip with an adhesive (e.g., Velcro). Users can create sentences by placing multiple cards containing pictures/icons for each word in the sentence onto the sentence strip (e.g., I + want + apple) and handing the sentence strip to their communication partner.

This AAC increases socialization between the AAC user and the communication partner, allows for an increased number of options, and can be adapted to the language level of each user. However, it can also be cumbersome to transport and, at times, to use. Additionally, it does require increased instruction for more complex uses.

Common modes of access

One of the first questions we should ask ourselves when we discuss an AAC candidate is “how would they be best able to utilize their AAC?” There are a few more common modes that are considered.

- Hands – Hands are a common mode of access for AAC use to activate a button on a tablet, press a button, give a picture/word card or even write and use ASL.

- Head – For an individual with inconsistent use of their hands or eyes, turning one’s head to hit a button is a practical option as long as they can consistently control neck movement. Head activated buttons can be used individually or to activate buttons on a tablet/device through a series of smaller choices which lead to the user’s final selection (e.g., selecting a row of icons followed by a specific icon).

- Eyes – Eye gaze is an AAC option for those who do not have the motoric capability to activate an AAC with their hands or neck but have the cognitive capacity to have increased options available and can consistently control eye movements.

Symbol types

Depending on the user, different symbols should be utilized for an AAC.

- Pictures of real objects – Especially for a new or younger AAC user, pictures of real and familiar objects can be very motivating, but they can be harder to generalize to larger concepts. Additionally, parts of language, including articles and prepositions, are more difficult or not possible to represent with real pictures.

- Symbols – Symbols come in many forms and levels of complexity. These provide a great way to visually represent a word, action, or preposition that can be more easily generalized to the larger group it represents.

- Words – Used more often by adults, words can also be used in place of a visual if a literate user prefers and is without reading deficits (e.g., Alexia).

Takeaway

People with a wide variety of circumstances utilize AACs of some form. It is important to recognize that an AAC user may have no cognitive impairment, but rather a motor impairment. Therefore, the use of an AAC does not imply a cognitive limitation. Overall, AAC comes in many forms and can be used by a variety of individuals. Speak with your speech-language pathologist to determine if your child is a candidate for AAC, which type is best, and how to use AAC to foster communication.